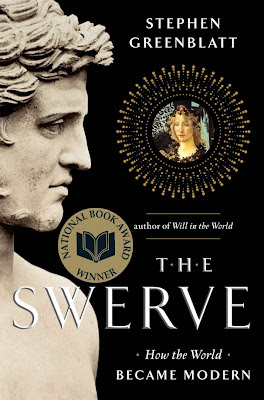

The Swerve by Stephen Greenblatt

Winner of the 2012 Pulitzer Prize

for General Nonfiction The Swerve by

Stephen Greenblatt reconstructs history by showing the reader the reciprocal

effect history and literature has on each other. Greenblatt re-imagines a time

when human civilization was emerging from the darkness by reaching back to the past

and uncovering the creation of the Renaissance and the Humanist’s movement. What

Greenblatt initially reveals is the beginning of the Early Modern Period

through ancient text. This book strikes a chord for book lovers, scholars;

classicist, early modernist, and even modern scholars. It conjures up a late

medieval romance of digging through monasteries and hidden chambers of West’s

past. This book works as a retelling of an archeological process illuminating

a story that has shaped the way our modern minds think. The struggle of a

secular society versus a religious society. It explores atheism, Christianity,

Paganism. Blending per-Christian ideas with a dominating Roman Catholic imperialism

of the fifteenth century.

Winner of the 2012 Pulitzer Prize

for General Nonfiction The Swerve by

Stephen Greenblatt reconstructs history by showing the reader the reciprocal

effect history and literature has on each other. Greenblatt re-imagines a time

when human civilization was emerging from the darkness by reaching back to the past

and uncovering the creation of the Renaissance and the Humanist’s movement. What

Greenblatt initially reveals is the beginning of the Early Modern Period

through ancient text. This book strikes a chord for book lovers, scholars;

classicist, early modernist, and even modern scholars. It conjures up a late

medieval romance of digging through monasteries and hidden chambers of West’s

past. This book works as a retelling of an archeological process illuminating

a story that has shaped the way our modern minds think. The struggle of a

secular society versus a religious society. It explores atheism, Christianity,

Paganism. Blending per-Christian ideas with a dominating Roman Catholic imperialism

of the fifteenth century.

It certainly has been a while since

I have picked up a nonfiction book. However, while I do a lot of focused

scholarly writing, I also spend a good amount of time reading essays and scholarly

criticism; never had I set down to read a complete nonfiction piece in the

past year of the magnitude. I have read Greenblatt’s Will in the World. It was a great read and

much praise to Greenblatt’s achievement and skills at recreating history for

his readers.

The big argument I feel that comes up with most of Greenblatt's work his is use of hedging and the use of possible—I thoroughly enjoy this style. Certainty for a history enthusiast they would question his development; I feel the work Greenblatt creates revives historical events and opens the past’s door for more scholarly inquires. With this form of Cultural Poetics an author can unravel the past, plus point out the untouched specks that have been brushed aside throughout history.

The big argument I feel that comes up with most of Greenblatt's work his is use of hedging and the use of possible—I thoroughly enjoy this style. Certainty for a history enthusiast they would question his development; I feel the work Greenblatt creates revives historical events and opens the past’s door for more scholarly inquires. With this form of Cultural Poetics an author can unravel the past, plus point out the untouched specks that have been brushed aside throughout history.

My initial reaction to The Swerve was the involvement the book

demands. The book, opens with a great story of a book hunter and immediately

the reader is transported back in time. This book achieves its goal of Greenblatt’s ever expanding

world of Cultural Poetics. He creates a world that is non linear, and unravels

the cause and effect approach to history. He allows the reader to enter the

minds of the great scholars of the past. Most importantly, Greenblatt makes you—me—want to

go book hunting. I recently went to a local used book store a couple of weeks ago and ran

across a Penguin Classics version of Lucretius’ On the Nature of the Universe

and immediately picked it up. Of course I haven’t fallen into to it yet but it certainly is on my list.

Initially, great scholarship makes you want to go back and read the works it criticizes and illuminates; The Swerve does just that.

There are few flaws as I will give this a five star rating. One flaw—I'm surely in no position to point out flaws in Greenblatt's work—he does leave a lot to be desired from a classical scholars point of view. Yes, it does make a classical scholar happy to know that one of theirs is responsible for the way we think today, but it does fall short in the department of really proving that and that might be case and point to read Lucretius in the first place. However, lovers of Classical Latin will enjoy the discussion and the amazing ability of the Early Modern Period's ways of text preservation. This books has something for every type of literary scholar and even any type of scholar in general. Great Author, Great Book.

Exerts:

"Humans, Aristotle wrote, are social animals: to realize one's nature as a human then was to participate in a group activity. And the activity of choice, for cultivated Romans, as for the Greeks before them, was discourse" (69). Greenblatt accentuates for the reader the connection of human interest—one being discourse. So when we think about the past or even the future, humans are always involved in a conversation either in the present or in the past whether we like it or not; we are always acting and reacting to what has come before in order to reveal what will come in the future.

"One simple name for the plague that Lucretius brought—a charge frequently leveled against him, when his poem began once again to be read—is atheism. But Lucretius was not in fact an atheist. He believed that the gods existed. But he also believed that, by virtue of being gods, they could not possibly be connected with human beings or with anything we do" (183). There are many moments throughout this book that give prominence to the lifestyle of past philosophers in conjunction with the Roman Catholic Church of the Renaissance while juxtaposing both of these worlds vividly. Greenblatt shows the contrast between the two worlds of thought and struggle which was contained in the power of words.

Initially, great scholarship makes you want to go back and read the works it criticizes and illuminates; The Swerve does just that.

There are few flaws as I will give this a five star rating. One flaw—I'm surely in no position to point out flaws in Greenblatt's work—he does leave a lot to be desired from a classical scholars point of view. Yes, it does make a classical scholar happy to know that one of theirs is responsible for the way we think today, but it does fall short in the department of really proving that and that might be case and point to read Lucretius in the first place. However, lovers of Classical Latin will enjoy the discussion and the amazing ability of the Early Modern Period's ways of text preservation. This books has something for every type of literary scholar and even any type of scholar in general. Great Author, Great Book.

Exerts:

"Humans, Aristotle wrote, are social animals: to realize one's nature as a human then was to participate in a group activity. And the activity of choice, for cultivated Romans, as for the Greeks before them, was discourse" (69). Greenblatt accentuates for the reader the connection of human interest—one being discourse. So when we think about the past or even the future, humans are always involved in a conversation either in the present or in the past whether we like it or not; we are always acting and reacting to what has come before in order to reveal what will come in the future.

"One simple name for the plague that Lucretius brought—a charge frequently leveled against him, when his poem began once again to be read—is atheism. But Lucretius was not in fact an atheist. He believed that the gods existed. But he also believed that, by virtue of being gods, they could not possibly be connected with human beings or with anything we do" (183). There are many moments throughout this book that give prominence to the lifestyle of past philosophers in conjunction with the Roman Catholic Church of the Renaissance while juxtaposing both of these worlds vividly. Greenblatt shows the contrast between the two worlds of thought and struggle which was contained in the power of words.

Greenblatt, Stephen. The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. New York: W.W. Norton &

Company, 2011. Print.

Comments

Post a Comment